|

COVER STORY Toxic Targets By Jim Motavalli

On September 10, 1997, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) head Carol Browner issued a simple but unprecedented order: She disallowed the state of Louisiana's approval of an enormous polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plant in Convent, a small, mostly African-American community already inundated with 10 other toxic waste producers. This by-no-means fatal blow to the Japanese-owned Shintech plant (the state can simply amend the filings) was nonetheless a shot across the bows of the waste industry, which has never before suffered such a setback at the hands of the federal government. Still pending against the Shintech application is a legal complaint, filed by the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic, charging that the state of Louisiana is in violation of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits any agency receiving federal funds from practicing racial discrimination. Does such prejudice exist in Convent? The average American is subject to 10 pounds of toxic chemical releases per year. The average Convent resident is exposed to 4,517 pounds, and that's before Shintech. In his office at Tulane University, Bob Kuehn, the tall, ascetic lawyer who heads the law clinic, doesn't look like a "vigilante" or one of the "big, fat professors who are drawing the big salaries," but that's what an enraged Governor Mike Foster, the recipient of a $5,000 Shintech campaign contribution, called him. "As goes the Shintech complaint, so goes many others," Kuehn says, pinpointing just why this case is so important and has mobilized such intense scrutiny. "This is the most watched and most significant case ever involving environmental racism," says Damu Smith, the southeastern regional representative of Greenpeace, which has worked closely with local activists. The term "environmental racism" wasn't in the vernacular until it appeared in a 1987 study by the United Church of Christ's Commission for Racial Justice entitled Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States. Ben Chavis, the commission's director, stated simply that "race is a major factor related to the presence of hazardous wastes in residential communities throughout the United States," and a new field of study was born. The pillars that allow pervasive environmental racism are beginning to crumble. In April, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission denied a license to a uranium enrichment plant impacting the African-American communities of Forest Grove and Center Springs, Louisiana. The prospect of a newly active federal government intervening to force environmental justice has led to increasingly desperate reactions from industry. Two prominent activists, Terri Swearingen, who fought tirelessly against a giant waste incinerator in East Liverpool, Ohio, winning the Goldman Environmental Prize for her work, and Phyllis Glazer, whose work is widely credited with helping close a toxic injection well in Winona, Texas, were hit with lawsuits by the companies involved. Such suits, designed to quiet crusaders, are known as SLAPPS, or Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation. It's not a coincidence that both SLAPPed activists are women, as are most of the people profiled in this special issue. Ask them why this is and you'll get a variety of answers, but the most common one is that women are nurturers who feel most deeply about building a future for their children and their community. And the stories told here are hardly unique: There are Convents and Winonas all over America. The WTI plant in East Liverpool, now up and running as one of the largest toxic waste incinerators in the U.S., is 1,100 feet from an elementary school. In New Orleans, activists are trying to relocate residents from the Agriculture Street Superfund site, where houses sit on top of a polluted landfill. In South Memphis, the closed and highly toxic Defense Depot is suspected of causing a cancer cluster among the African-American residents. In California, Florida and other states, migrant agricultural workers ingest unsafe levels of pesticides while working for subsistence wages. In many states (particularly Texas and Louisiana), state environmental departments compound the problem by seeing themselves more as extensions of industry than watchdogs for clean air and water. It can be disheartening to learn that, 28 years after the first Earth Day, such conditions still exist, but the good news is that people are fighting back, and--for once--the law may be on their side. Alsen and Convent, Louisiana: On Cancer Alley

If ever a road was misnamed a "Scenic Highway," it's the route to Alsen, Louisiana, an unincorporated corner of north Baton Rouge. The two distinguishing features are boarded-up retail businesses and gigantic chemical plants, most with manicured lawns. In Alsen, a low-income community of 1,500 that is 98.9 percent African-American, Rollins Environmental Services built in 1970 the fourth-largest hazardous waste landfill in the U.S. According to Unequal Protection: Environmental Justice and Communities of Color by Robert Bullard (see Conversations this issue), the now-closed facility was cited for violating state and federal environmental laws more than 100 times between 1980 and 1985. Alsen residents began reporting headaches, chronic fatigue, cancer and spontaneous nosebleeds. According to one study, 80 percent have respiratory problems, and 21 percent have asthma. In a vivid demonstration of the principle that "waste follows waste," Alsen was soon inundated with chemical industries. There are plastics plants, lead smelters, landfills, tank car washers, petroleum coke yards, resin makers and two Superfund sites. In 1995, some 57 million pounds of wastes were released in East Baton Rouge parish, according to EPA data.

Polluters have had a free reign in Alsen, but that may be changing. Two proposed landfills in town are having trouble getting licensed. "We have been 'dumped' on too much," reads an open letter sent by residents to the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ). Now represented by the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic, the activists of the North Baton Rouge Environmental Association (NBREA) are finally being heard. Juanita Stewart, NBREA's wild-eyed and energetic president, has trouble sitting still in her small house on Old Rafe Mile Road. She's full of outrage and anecdotes about injustice: the white particles that fall on everything, the rumbling trucks that leave clouds of dust, the health problems. Shirley Brooks, secretary-treasurer of an organization with very little money, is quieter. They both readily admit that Alsen is a community divided. In 1981, a group of residents organized a $3 billion class-action suit against Rollins but, in 1987, settled for far less. Residents who got $500 to $3,000 signed away their rights to sue again; some of them turned from company critics to company defenders. There's bitterness between them and NBREA, which says it isn't motivated by money, but by fighting for a cleaner Alsen. It is only a short distance from Alsen to Convent, another Cancer Alley town, and the communities have much in common, though Convent, which has 10 chemical plants that employ very few of the town's African-Americans (there is 60 percent unemployment) is now much better known. If St. James Citizens for Jobs and the Environment, aided by partners like Greenpeace and the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic, succeed in stopping Shintech, a mammoth, Japanese-owned plastics factory, they will have made history (see introduction). Their activism has drawn rebukes from the hyperventilating governor, Mike Foster, and from state Department of Environmental Quality spokeswoman Janice Dickerson, who called them "little Hitlers." Like most environmental justice groups, St. James Citizens is a small band of mostly female, mostly elderly residents outraged at the contrast between the community they grew up in--usually rural and bucolic--and the wasteland it's become. Three of its principals, Emelda West, Gloria Roberts and Rose Ann Rousell, all Convent natives, offered a brief guided tour that was like a descent into Hell. Convent, surrounded by graceful plantations and a religious retreat house that must do some selling job, is choking on poisons; there's an environmental insult lurking behind every trailer home. In 1994, the EPA recorded more than 60 hazardous waste spills in Convent, ranging from chlorine and ammonia to hydrogen sulfide and waste oil.

Behind one of two plants owned by IMC-Agrico, a maker of chemical fertilizer, is a towering stack of white gypsum, extending several miles and butting up against a sugar cane field. Instead of removing the gypsum byproduct, which residents say sometimes goes airborne and creates choking dust, IMC has instead planted grass on part of it, creating a golf course effect. On Easter Sunday this year, a huge fire at Star Enterprises (formerly Texaco), sent people scurrying for safety instead of reporting to church. The Romeville Elementary School is only a few miles from the plants, and it's even closer to the large field (a rare green space in Convent) that's the "future home" of Shintech. A St. James Citizens activist named Mary Louise Green stood in the front yard of her home on a rutted road in Convent and pointed at the men working, literally in her back yard, cleaning toxic waste out of tank cars. "Don't ask me about no Shintech," she says. "I hope they stay in Japan. The companies come here, then go 10 years without paying taxes. They don't offer many jobs, and the ones they have don't go to people around here. Our kids could walk there, but they don't work in the plants." Everything you need to know about Convent can be learned by looking at a map prepared by the Port of New Orleans, showing the town's 11 existing chemical plants in blue. In red, an even greater number of sites are proposed or pending. Gloria Roberts, a dignified former teacher, looks down the pockmarked road at a forlorn government housing project, with broken windows and idle men sitting on front porches. "This is what 40 years of economic development has done for the African-American community in Convent, Louisiana," she says.

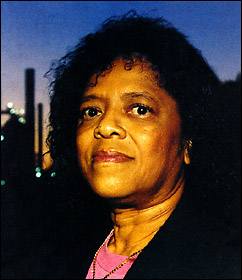

Norco, Louisiana: "The Flames of Shell Are Flames of Hell"* It may not have been living for most of her life next to a gigantic Shell chemical plant that gave Margie Richard religion, but it certainly could have been. Her small trailer is directly across the street from a mammoth Shell oil refinery and chemical plant, a complex so big it resembles a small city. (Indeed, the plant is the city: "Norco" stands for New Orleans Refining Company, the name of the factory before it was bought by Shell in the 1920s.) Flares burn off into the night, and a pervasive stench, like burning plastic, fills the air. Notations on pipelines indicate they carry ethane, chlorine, ethylene and propylene. Walking down her street, Richard passes the grown-over home foundation of her late sister, who died of sarcoidosis in 1983 after selling her home to Shell. There are many similar foundations on the street, all representing people who died or moved away.

Only a narrow street separates Diamond, an African-American At the end of the street, a playground is all that's left of an elementary school that's also among the missing. Fourteen-year-old Artie Wooten is playing basketball with the plant as a dramatic backdrop. "They should clean up this place," he says. "It hurts my nose." About 20 feet from where his ball bounces against the backstop is a square depression in the earth, a reminder of the flying object that landed there last February. A large piece of metal handrail, four feet across, was blown off a Shell tank, burying itself deep into the playground. Company representatives came and took it away, later admitting that existing safety mechanisms had failed.

The plight of the 500, mostly African-American people who live in Norco's Diamond community has seldom made headlines. No rock stars have held benefits for them, and they have no wealthy benefactors. But their situation is no less egregious; in many ways, this tiny enclave in the middle of "Cancer Alley," the toxic stretch of the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, stands alone in terms of blatant shock value. Dr. Beverly Wright, who heads the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice at Xavier University in New Orleans, says she took an international delegation to Norco, and a visitor from Nigeria, where Shell's oil operations have been widely condemned and the company has been accused of culpability in the death of Ogoni environmental leader Ken Saro-Wiwa, "couldn't believe that something like this existed in the United States." A St. Charles Parish jury didn't agree. Last August, it deliberated for less than two hours before deciding that Shell Norco, which makes specialty resins and covers 900 acres, does not "pose a nuisance" to Diamond. Residents, led by Richard and Norco Concerned Citizens, charged that they'd been plagued by the noise, smells, soot and intense 24-hour lights from the plant; they asked for damages and wanted the company to pay for a mass relocation. Shell's air-quality experts convinced the jury that the giant chemical operation posed no threat to the residents, and that the suit was motivated solely by an effort to plumb the company's "deep pockets." Shell attorney Mark Marino said during closing arguments, "We all live in a society that has to tolerate certain inconveniences." Margie Richard's grandchildren, Chris and Josh, say there's not many places for them to play outside, with the plant's barbed wire fence just 20 feet from the front yard. Joseph Johns, 17, was just mowing his lawn one day in 1973, when an explosion at the plant left him with third-degree burns (an elderly resident was also reportedly killed by the blast). A 1988 explosion at a second Shell facility shook the whole town, says Richard, adding that her own parents, children and grandchildren have been afflicted with emphysema, allergies, asthma and skin rashes. These maladies are common in Diamond, as is cancer. Some people have taken the money and run. Shell buys people's houses, with the going rate about $10,000 to $15,000 for a trailer and $45,000 for brick homes--not enough to get established somewhere else, residents say. A pile of rubble is all that's left of Richard's neighbors' home. The company says these purchases have nothing to do with dangers from the plant, but are to help it build a "green belt." Richard, a former teacher and drug counselor who is now studying for the ministry, did move away for a while, but she came back as a committed activist. "I made a sacrifice to come back here," she says, "but these are my people, and I believe in the God-given principles about institutions of sin. I wouldn't be able to endure this without faith. Nobody has the right to get rich at the expense of other people's health."

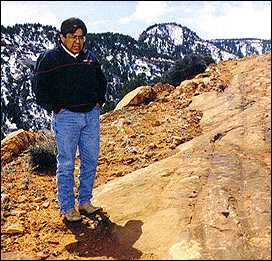

* Lyrics from a Nigerian song. Shiprock, New Mexico: Native Injustice Phil Harrison, Jr. was working the phones, trying to arrange transportation for a Native American delegation whose arrival from Canada was imminent. The soft-spoken Navajo with a wry sense of humor, whose tiny office is tucked into a trailer near the government-run Shiprock Hospital, had 48 hours to get people mobilized for what would probably be the most important meeting of his life. For the past 17 years, Phil Harrison has been fighting to win environmental justice for the 3,000 Navajo uranium miners who worked the pits in New Mexico and Arizona for 50 years beginning in the late 1930s. Surviving miners say they were never told by the mine operators, including Union Carbide and Kerr McGee (employer of the late Karen Silkwood), that uranium was dangerous. And so they blasted it out of the rock face with dynamite, dug it out with shovels, let their children play with it, and built their houses on its tailings. Phil Harrison remembers, as a child, chewing on those tailings. "They tasted sweet," he said. The claim that the companies themselves didn't know about the dangers doesn't stand up to scrutiny. Hundreds of European uranium miners--more than half those working--died of lung cancer after being exposed to radon in the 1920s, as was noted in a 1952 report from the U.S. Public Health Service. In addition to radiation and dust, miners were exposed to some 36 toxic chemicals. Harrison's father was a uranium miner, and lung cancer claimed him in 1971. Cancer got five of his uncles, too, as well as hundreds of other former miners around Shiprock. Today, this seat of the Navajo nation is ailing; it leads the region in unemployment, alcohol addiction, traffic accidents and violent crime. For many years, the miners' plight went unrecognized and uncompensated, but now that's changing. Harrison formed the Uranium Radiation Victims Committee in the early 1980s, and it and other activist groups lobbied for federal recognition. They got it in 1990, when Congress passed the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA). If they qualified, former miners could receive as much as $100,000 for their ailments. If they qualified. RECA determines eligibility by a rather arcane formula (based on "working level months," calculated from time spent underground and the relative toxicity of the site). Only non-smoking miners suffering from cancer or other malignant respiratory diseases who worked between 1947 and 1971 have any hope of qualifying. But mining operations continued much later than 1971. In Shiprock they stopped in 1966, but in Colorado and Utah mining went on until 1990. "You have to have one foot in the ground or actually be dead to make a claim," Harrison says. Since the bill became law, less than 500 people have been compensated, 400 have been denied and another 400 cases are pending. In the last 45 days, Harrison adds, eight former miners got lucky--they died, speeding up their claim for benefits. Mostly, it's lung cancer that kills them, but there's also pneumonia, silicosis and leukemia, Harrison explains.

There remain many sick, uncompensated miners in and around Shiprock. Some of them worked aboveground milling uranium--directly handling it, without masks or gloves. Tall and lean Willie Johnson, 64, is chapter president of the Red Valley Senior Citizens Center, and drives a lot of elderly Navajo with breathing problems to Shiprock Hospital. Sitting among crates of canned food, Johnson talks about his school days, when he'd work two months at a time down in the mine to help pay for his education. "We'd dig out the uranium with a shovel and a pick, dump it in the car and send it out," he says. "No one told us that mining was dangerous. We wore hard hats and steel-toed shoes, no protective clothing. There was never enough ventilation down there, and lots of dust." But, Johnson says, it was a good-paying job, and there were precious few of those around Shiprock. It wasn't until 1970, Johnson says, that he first heard that mining was dangerous. Now Johnson is sick himself. Five years ago, he was diagnosed with silicosis, a lung fibrosis caused by dust inhalation. But as he worked the mines summers only, Johnson doesn't have enough working level months to qualify for compensation. "Justice closes down if you didn't work long enough," he says. Inside the center's main hall, sits George Tsosie, 61, a grizzled former miner in a baseball hat who bears some resemblance to Adam Clayton Powell. Tsosie spent nine years in the mines, ending in 1971. Speaking in the soft burr of the Navajo tongue, Tsosie says he was inaccurately designated a smoker on official forms, disqualifying him from the compensation he would otherwise have been entitled to get. The Indian Health Service told Tsosie, a former drill operator, that he has an abnormal lung condition, and he suffers from shortness of breath, and skin problems. Only five of the 15 men he worked underground with are still alive. "There were no warnings about the dangers," Tsosie says. "And only in later years was there enough ventilation." A onetime Kerr McGee employee, Tsosie adds that health insurance was not part of the package. The 1990 law hasn't had the impact its supporters had hoped, and that brings us back to the April 18 hearing, which drew 1,000 people to Fort Wingate High School ("Home of the Bears") in Gallup. Working together, the New Mexico Uranium Workers Council, the Uranium Radiation Victims Committee and the Navajo Office of Uranium Workers have come up with a proposed revision to RECA that would increase benefits (to as much as $200,000) for a much wider group of former uranium workers. Called the "Radiation Workers Justice Act of 1998," the bill was introduced into Congress by Representative Bill Redmond (R-NM). According to Cooper Brown of the Washington law firm Cummins and Brown, which consults with the Navajos on radiation rights litigation, the bill would: extend the covered period to 1990; widen the range of recognized illnesses; lower the number of required working level months; and include surface miners and millers. The President's Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments wrote in a 1995 final report to President Clinton, "The grave injustice that the government did to the uranium miners, by failing to take action to control the hazard and by failing to warn the miners of the hazard, should not be compounded by unreasonable barriers to receiving the compensation the miners deserve for the wrongs and harms inflicted on them as they served their country." But that's an advisory committee. Getting a bill passed in the real world is another matter. "It will be an interesting little battle," says Brown, who notes that the Clinton administration, usually sympathetic to Native American claims, is often opposed in practice by its own Justice Department, which has "a different agenda" and is likely to bitterly oppose extension of miners' rights. So far, H.R. 3439 has only two cosponsors, one of whom is deceased, so getting the Act through Congress may be an uphill fight. If the Act becomes law, Phil Harrison says he'll see it as a vindication of his life's work, which has already cost the support of his family and any semblance of a stable income. "I've lost a lot, 17 years of my life," Harrison says. "But if this bill goes through and I see people finally getting compensation, it will have been worth it." Tragically, it still would not be the end of the story. Uranium mining on Navajo land is alive and well, thanks to a proposal from Hydro Resources, Inc. (a subsidiary of Dallas-based Uranium Resources, Inc.) to drill uranium mines and operate processing plants at Church Rock and Crownpoint, New Mexico, east of Shiprock. This so-called leach mining will not involve sub-surface workers, but it is very water-intensive, and the Navajo worry it will pollute their acquifer. Despite their fears, the mines are almost fully licensed. "I know that people are worried about the water, but there's really no chance that what we do will affect it," says Hydro Resources' Frank Lichnovsky. "There's no danger." And that, say the Navajos, is something they've heard before.

Winona, Texas: Thrown Down the Well Phyllis Glazer's Blazing Saddles Ranch covers 2,200 acres that seem to stretch endlessly to the horizon in the lush, well-watered country an hour and a half east of Dallas. Dotted by emus, exotic donkeys, zebras and horses, the property (which once belonged to oilman H.L. Hunt) looks like a cowboy's idea of paradise. And Glazer, who has an obsession with western memorabilia and dresses like a cowgirl, says that when she bought the ranch in 1988, that's exactly what it was. But this paradise has a snake in it. Looking around her spread today, Glazer sighs and calls it "2,200 acres of environmental liability." Only a few miles from Blazing Saddles, through the boarded-up remains of what was once the thriving town of Winona, is a half-dismantled industrial plant run by a skeletal staff of eight. This was the site of Gibraltar Chemical Resources, Inc., later American Ecology, a deep-well injection site for hazardous wastes. From 1981, when it opened, to 1997, when it closed, trucks from all over the region lined up to dump hundreds of tons of toxic material down the narrow, one-mile-deep twin shafts, where it supposedly was held in an impermeable rock formation. But the safety of such wells is in question. According to a report from the Virginia-based Center for Health, Environment and Justice, "Supporters of deep wells say there are no documented examples of groundwater contamination from leaking underground wells. This is false." The report goes on to list cases of just such failures in Alabama, Florida, Louisiana and North Carolina.

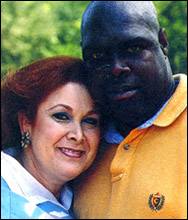

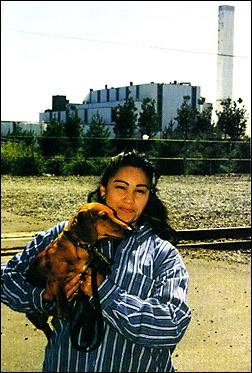

Phyllis Glazer and Winona resident Tommy Bland at her Blazing

Saddles Ranch, which she calls Phyllis Glazer didn't know about Gibraltar when she bought her ranch; if she had known, she probably would have passed on the purchase and gone on with her comfortable life in Dallas. And that, nearly everyone agrees, would have made life much simpler for Gibraltar Chemical and American Ecology. Without any history of activism, Glazer founded Mothers Organized to Stop Environmental Sins (M.O.S.E.S), dedicated to fighting for Winona's mostly poor and minority families. And they needed a lot of help, for not only had their previous attempts to organize against the plant gone nowhere, but an increasing number of people were sick. Glazer's commitment--and money--made a big difference in the war against the wells, ultimately leading (many observers believe) to their closure. American Ecology's response was a multi-million dollar lawsuit against Glazer, her husband (who runs a large liquor wholesale business), and even her uninvolved mother. It's impossible to prove that American Ecology's wells made people sick in Winona, but there's no doubt that this is a very unhealthy community, stalked by cancer, lupus, albinism, respiratory problems and multiple chemical sensitivity. Hud Clarke, a handyman who once worked for H.L. Hunt and lives directly downwind of the plant, is a big sad-eyed black man in a cowboy hat. There's nothing soft about him, but a stutter and still-evident deep grieving make it difficult for him to talk about the loss of his 11-year-old daughter, Mandy, to Hodgkin's disease last year. She was eight when she first got sick with breathing problems. A round of doctors in Tyler and Dallas put her through a debilitating round of chemotherapy. In an existing photo of her taken by Tammy Cromer-Campbell, Mandy hides her face in her hands, afraid to show what drugs and disease had done to her. Anita Lamb, a small, nervous woman with cropped hair, is only 39, but has a list of chronic ailments that usually turn up in people much older. Lamb, who can't work, says she has frequent migraine headaches, respiratory infections, osteoporosis, short-term memory loss and anemia. She was diagnosed with chronic lupus, a serious ailment that attacks muscles and mucous membranes and is often seen in heavily polluted environments, in 1996. Lamb believes that "85 percent of what's wrong with me is because of that plant. The doctors won't say it's definitely because of exposure to chemicals, but that's what I believe. They should pay our medical bills, because we were damaged for the rest of our lives." Lamb, like Clarke and many other residents of Winona, says she was not told the real story about what was going on at the plant until some years after it opened. She points to newspaper stories that said Gibraltar was building salt water injection wells, a common extension of the oil industry that surrounds Winona. The stories also said Gibraltar would plant orchards on the hundreds of acres surrounding the plant. The orchards never arrived, but a sense that something was seriously wrong definitely did. Some say it was first noticeable in the animals, which mysteriously died or gave birth to deformed, two-headed or stillborn offspring. "When we hung our clothes on the line, they would smell like chemicals," says Charles Sharpe, a dignified septuagenarian and church elder. "And then we started getting sickness in our community. And people started dying, many of them younger than me." Sharpe himself saw his once burly 269 pounds dwindle to 155. The extremely close-knit, self-reliant Shaddox family moved to Winona in 1981, the year the plant was built, to get away from the city and breathe fresh air. They bought an old farmhouse and rebuilt it board by board, planted a garden, then started a home-schooling program for Katie, now 14 and recovering from multiple chemical sensitivity (MCS), and Cassie, 9. Their country getaway was soon like an urban war zone. "We would catch these terrible smells from the plant, then check the wind direction," says Joey Shaddox, a local postman. "We called the state Texas Natural Resources Conservation Commission all the time, but they'd either not come or say they couldn't smell anything." Sharon Shaddox adds, "It was a feeling of helplessness. We'd keep the kids' school books in baskets so we could evacuate at a moment's notice." Ironically, they'd go back to polluted Dallas so they could breathe again. The Shaddoxes want to think that the plant's closing will bring back the life they lost, but the waste buried at Gibraltar is still underneath their town. They want a town where people live in harmony, but they got one with a wedge driven through it, as some people make peace with the company and turn up driving new pickups, and others fight on. Winona might have seen Gibraltar and its 200 jobs as the first outpost of an economic renaissance for the town, but the opposite happened. Dale Wright, Winona's postmaster and its former mayor, takes visitors through what was once the fried pie capital of East Texas and host of a famous country music event called the Winona Hoedown. Wright, who endured chronic nose bleeds and a deviated septum, walks down a main street filled with boarded-up stores, pointing out a once-bustling grocery whose dusty interior still features neat rows of carts and ads for produce specials. He pauses in front of a cavernous space littered with rubble and says it was once full of hardware and old men playing dominoes. A sign in the padlocked door says, "OPEN: YA'LL COM' ON IN." In three blocks of blank windows, only O'Dell's Pizza is open for business. Owner Jodie Jones, who recently moved to town from Wyoming, says she wishes the plant was still open, "because at least then, they'd be monitoring the wells." They're supposedly monitoring them now. American Ecology, whose subsidiary is fighting environmentalists in an effort to build a low-level radioactive waste dump in Ward Valley, California, is still a presence in Winona, though a ghostly one. The air around the plant is clear now, with few signs of the rust-colored smoke clouds that residents say they used to drive through on the public road. The remaining workers spend their days carting off leftover sheet metal. The surrounding woods, site of the supposed orchard, have been messily logged. Inquiries in the plant office, which is decorated with pictures of the Little League teams the company sponsored, draw referrals to the Boise, Idaho office of Scott Peyron and Associates. "There is no factual basis for any claim that Phyllis Glazer has made," Peyron says, declining to comment further. "The matter is in litigation, and it's for the courts to decide." Glazer has health problems of her own, including numbness in her feet and short-term memory loss. But despite the fact that she's gone through a large inheritance fighting Gibraltar and American Ecology, Glazer is undeterred--and still very emotionally committed to Winona and its struggle. "Winona is known as a black town and a poor town," she says. "The people can't afford to pay their M.O.S.E.S. dues, but they bring me food and gave me a lot of support when things got really bad here. I've been shot at, had my animals killed. Trucks have tried to run me off the road. It's calmed down a bit since then." Glazer has taken wide-eyed Winona delegations to Austin and, on two occasions, to Washington, D.C., helping to make this one of the better-publicized environmental justice cases. When, three years ago, more than 100 people marched down Texas Highway 155, singing "Go Down Moses" on their way to rededicate a desecrated slave cemetery on American Ecology property, it got people's attention. Meanwhile, property values have plummeted in Winona, and nobody is celebrating the plant's closure. People are still sick and dying, and a thicket of lawsuits keeps everyone occupied. A $200 million class-action suit against the plant is pending, as is the suit against Glazer and her family. The case has consumed her life. Glazer's attorneys sometimes bristle at her tendency to talk first and consult them later, but they've learned to live with it. This particular volcano won't easily be capped.

Chicago, Illinois: Gardens of Waste

At first glance, Altgeld Gardens, a public housing project on Chicago's Southeast Side, appears benign. As you exit the expressway, you enter an open, sunlit area without the congestion of the city center. On the right are rolling hills dotted with bushes, some in full pink blossom. On the left, tulips have been planted in the grassy knoll at the entrance to the winding rows of yellow-brick townhouse-style housing. In fact, Altgeld Gardens sits in the center of a toxic doughnut of heavy industry and waste dumps. The leafy hill conceals a mammoth water-treatment plant with acres of sludge-drying beds. Spread out in other directions are more than 100 industrial plants and 50 active or closed waste dumps. The area contains 90 percent of the city's landfills. Altgeld Gardens, whose 10,000 residents are virtually all African-American, was itself built on the edge of an old industrial waste dump. Residents are subjected to an assortment of nauseating odors from the surrounding water-treatment plant, landfills, steel mills, and chemical and paint factories. "One night last summer, I woke up smelling butane gas," recalls resident Hazel Johnson, founder of People for Community Recovery, the nation's only environmental justice organization based in a public housing project. "I asked my daughter to go to the kitchen to check the stove, but the smell was coming from Waste Management's landfill."

The waste dumps leak toxic chemicals into the groundwater as well as local lakes and rivers. On a sunny April afternoon, fishermen set up their poles on the banks of the debris-strewn Little Calumet River, ignoring the oily tincture of the water. For years, poor black families at Maryland Manors, abutting the southern edge of Altgeld Gardens, drank well water that was laced with cyanide, benzene and toluene. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Chicago's Southeast Side has the city's highest concentration of ambient lead, and the second-highest concentration of fine dust particles. These air-borne pollutants cause a host of ailments: watery and burning eyes, skin rashes, conjunctivitis, asthma and other respiratory illnesses. Residents also suffer from high rates of prostate, bladder and lung cancers. People for Community Recovery, working with other environmental groups like the Southeast Environmental Task Force, has gone up against some of the area's industrial behemoths--and won some key battles. A Waste Management incinerator was shut down, and company plans to build a landfill were blocked. As part of consent decrees, the EPA can demand that industrial polluters fund environmental projects, and the Chicago-based Citizens for a Better Environment (CBE) has been working with community groups on the Southeast Side to identify worthy projects "so the money stays in the polluted community, rather than going into the federal treasury," says Scott Sederstrom, a CBE organizer. One block from Hazel Johnson's office, across from a Headstart program, is a vacant yard, where the Chicago Housing Authority stored its used transformers. Dangerous levels of PCBs have been recorded at the site, but the clean-up job, estimated to cost $5 million, is moving slowly, with the site barely protected by a corrugated metal and wood-slate fence. Johnson's daughter, Cheryl, shows photos of a 10-inch opening in the fence. "I've seen kids playing around there," she says. "They call that inaccessible?"

Bridgeport, Connecticut: Caught in a Vice Glenda Noblin remembers when kids used to play Little League in the field across from her home on Seaview Avenue in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Now the field, ringed by barbed wire, is a littered wasteland. Kids play in the busy street, where they dodge the big trucks servicing the many heavy industries that ring Noblin's increasingly embattled, mostly minority neighborhood. "I feel like we're caught in a vice," says Noblin, a high school teacher, as her daughter, Jaree, climbs the one spindly tree that manages to survive amid the polluted air, constant dust and foundation-cracking vibration of her front yard. From her perch, Jaree, who is eight, can just see a glimmer of Long Island Sound through a forest of oil barge platforms, warehouse storage yards, stacks of sewer pipes and spent fuel tanks. A few years ago, she would have been able to picnic and chase horseshoe crabs on nearby Pleasure Beach island, but the rickety old bridge--the neighborhood's only beach access--is out of commission with no repair in sight. John Percell, who's lived his whole life on Seaview Avenue, says he remembers when this part of the city's East End was a beautiful coastal community. Now 43, he looks out on the giant tanks of Advanced Liquid Recycling--"a full-service waste treatment...business serving the auto industry." But Percell may soon have an even closer neighbor--an asphalt plant.

The plant is one of two--both in mixed Hispanic and African-American neighborhoods--whose applications recently turned the city of Bridgeport upside down. Residents, who have watched their communities gradually deteriorate as dirty industries profited, are taking a stand. They came out in force, 600 strong, to a recent public hearing on the proposal. As attorneys defending the proposal droned on into the night, neighborhood kids, proud of their sudden celebrity, marched through the Common Council chambers carrying signs with messages like "I Don't Smoke, Drink or Breathe in Asphalt Fumes." Even if the proposed plants are as quiet and environmentally self-contained as their defenders say they are, there would still be considerable concern about the so-called "fugitive emissions" rising from the asphalt-carrying trucks that would use residential streets. Citing grassroots health initiatives that kept out asphalt plants in Massachusetts and in North Carolina, state representative Chris Caruso noted Bridgeport's elevated levels of bronchitis, asthma and emphysema. Indeed, a recent Bridgeport Community Health Profile found that 21 percent of the households surveyed had kids with asthma, three times the U.S. average. "It's ridiculous, an insult," says Hispanic community activist Willie Matos, who adds that the Strategic Plan for the city that he helped devise calls for clean industries only. Shirley Bean, a councilwoman given to extravagant hats who is also a near-lifelong resident of Seaview Avenue, thundered at an impassive Planning and Zoning Commission. "We do not need an asphalt plant next to residential housing, where children are playing and going to school." There's nothing new about dumping on Bridgeport. The existence of a 100-foot-tall "Mount Trashmore" on the city's East Side brought Jesse Jackson to town in the early 90s for a march against pollution. Illegal dumps are common, as are brownfield sites--the closed and contaminated plants that are the legacy of a once-vibrant manufacturing city. Now the Resco "garbage-to-energy" incinerator dominates the city skyline from its position in the city's African-American and Hispanic west side, and residents are fighting a huge expansion of the local utility's mostly coal-fired electric plants. "They call Bridgeport 'the armpit of the East,'" Percell told a weekend rally in front of his home. "They keep bringing in dirtier and dirtier proposals, and Mayor Joe Ganim [the recipient of both asphalt developers' campaign largesse] keeps giving them what they want." Joe Ganim finally did come out against the asphalt plants--on the day the state Senate voted to impose a two-year statewide moratorium on their construction. Too little, too late, say the asphalt activists, who point out that the mayor only took a stand when the plants were politically dead. As for the asphalt developers, both of whom live out of town, Jaree Noblin says "maybe they'd feel differently about it if they had to live here."

Chester, Pennsylvania: Waste and Corruption Chester, a hard-hit small city 10 miles south of Philadelphia, is more than 60 percent African-American and has a profusion of waste treatment facilities. It's "governed" by a Republican political machine that's been in near-continuous control of the city for more than 130 years. George magazine named Chester one of "the 10 most corrupt cities in America," and in the last 20 years a former mayor has been convicted of bribery, racketeering and conspiracy; a former police chief was found guilty of numbers running; and a former councilman went to jail for theft, criminal solicitation and other crimes. Perhaps afraid to expose itself to too much democracy, the city council meets on weekday mornings. The current mayor, Aaron Wilson, Jr., took a city resident to court after she tried--and failed--to get him to reveal his position on a proposed soil processing plant. A man identified in a 1990 Pennsylvania Crime Commission report as "the principal Black racketeer in Chester, " dealing in drugs and loansharking, was recently appointed as building supervisor in the Parks and Recreation Department. A defeated air hangs over Chester like a toxic cloud. On a recent bright Saturday morning, downtown Chester sat mostly boarded up, with the only steady traffic coming from the storefront office of Chester Residents Concerned for Quality Living (CRCQL), a virtually one-woman operation run by a powerhouse named Zulene Mayfield. When she's not wiping runny noses on the kids who come in for afternoon environmental education classes, she's taking visitors on walking tours of her besieged neighborhood.

As Mayfield points out with characteristic outrage, Chester is the dumping ground for Delaware County (which includes such wealthy college towns as Swarthmore, Bryn Mawr and Haverford). Sun Oil and British Petroleum operate storage tanks and refineries in Chester, and there is also McCusker and Sons, a commercial transfer station that processes 150,000 tons of waste per year; the Delcora sewage treatment plant and sludge incinerator (an arsenic emitter); Thermal Pure (not currently operating), the biggest medical waste processor in the nation; and the mammoth American Ref-Fuel, the fourth-largest solid waste incinerator in the U.S. These corporations do more than enrich Chester's tax base. They're also polluters, processing 2.2 million tons of waste per year and contributing to the fact that 90 percent of all the toxic chemicals released in Delaware County come from the Chester area. Without a doubt, Chester is an unhealthy place to live. It has the highest infant mortality rate in the state, the highest percentage of low birthweight babies, and an elevated lung cancer rate. According to a 1994 EPA report, 60 percent of Chester's children have unsafe blood lead levels. To visualize American Ref-Fuel, picture a complex the size of four football fields, surrounded by an "ornamental" row of crazily twisted and stunted pine trees, which residents say die every few years and are replaced. Just up the street, men fish in the Delaware River, under a graffiti-covered sign warning them not to eat their catch. The plant emits a steady roar, which is punctuated by the rumble of the 400 18-wheel trucks (some of which lack legally required markings, Mayfield says) that follow routes through city streets every day. Neighborhood resident Shantae Burrows, a lively 10-year-old, says she "always looks both ways, because those trucks, they're going all fast--somebody's gonna get hit." The trucks also drip what Shantae calls "trash juice," a sticky liquid that coats streets and sidewalks. Lisa Gilliam, a 35-year-old computer programmer and mother of two who's also a diabetic, knows all about trash juice; the house she owns is directly across the street from American Ref-Fuel. For the last two years, Gilliam says, she's been "feeling just bad, tired and weak. I keep colds forever." Her daughter, who's nine, has also had respiratory problems and developed persistent warts all over her hands. Gilliam says that sometimes the "air gets different," there's a terrible smell and a stinging in her eyes. Dust settles on everything, forcing her to clean her immaculate rowhouse daily, and wash off the black soot that collects on her car. But the impression that Chester is being slowly poisoned by chemical plants and incinerators is actually a misleading one, says Steve Simmons, business manager for American Ref-Fuel. The dust people complain about is actually from a nearby construction demolition business. The emissions violations which drew fines of more than $400,000 are in the past, he adds, from the era when Westinghouse owned the plant. American Ref-Fuel today, he says, "has no visible emissions." It does, he admits, pour forth volatile organic compounds (VOCs), dioxin, nitrous oxide, sulfur oxide, lead and other heavy metals, but, because of the plant's scrubbers, the toxins emerge "only in trace amounts, below any level thought to generate a health problem." In fact, says Simmons, "The health risk is four times less than it would be from eating a peanut butter sandwich every day." Lisa Gilliam is not reassured. She wants out of Chester. After years of fruitless fighting, endless meetings in which Gilliam says she was condescended to by company officials, "I want to just go. My priority is to get my kids out of here." But Gilliam's "five-year plan" may have to be extended. Who's going to buy a house next door to the fourth-largest waste incinerator in America? Even as good people like Gilliam flee, Zulene Mayfield says she's staying. Walking back from the plant, she stops a dozen times to talk to city residents, arranging activities for footloose kids, urging adults to come to public hearings and meetings. She keeps her storefront, a community center for a town that desperately needs one, open on a minuscule $16,000 a year, enduring frequent intimidation (including two break-ins that left the letters "KKK" still visible on her wall). "I'm not a mother, so my situation is different from Lisa's," Mayfield says. "If we all go, who'll fight these people?" Chester's voices are finally being heard. In 1996, when Cherokee Environmental Group proposed a contaminated soil processing plant in Chester (prompting a public hearing last February that no member of the city council bothered to attend), Mayfield took the state of Pennsylvania's Department of Environmental Protection to federal court. The suit, the first of its kind in the nation, was filed under Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, charging the DEP with racial discrimination in its permitting process. Soon after, in a move very likely influenced by citizen pressure, the DEP denied Cherokee's permit (the first time it had failed to license any Chester waste facility). Late last year, a federal judge ruled the environmental racism suit against the state could proceed.

JIM MOTAVALLI is the Editor of E.

© 1990-1999, Earth Action Network Updated by webmaster@emagazine.com http://www.emagazine.com |